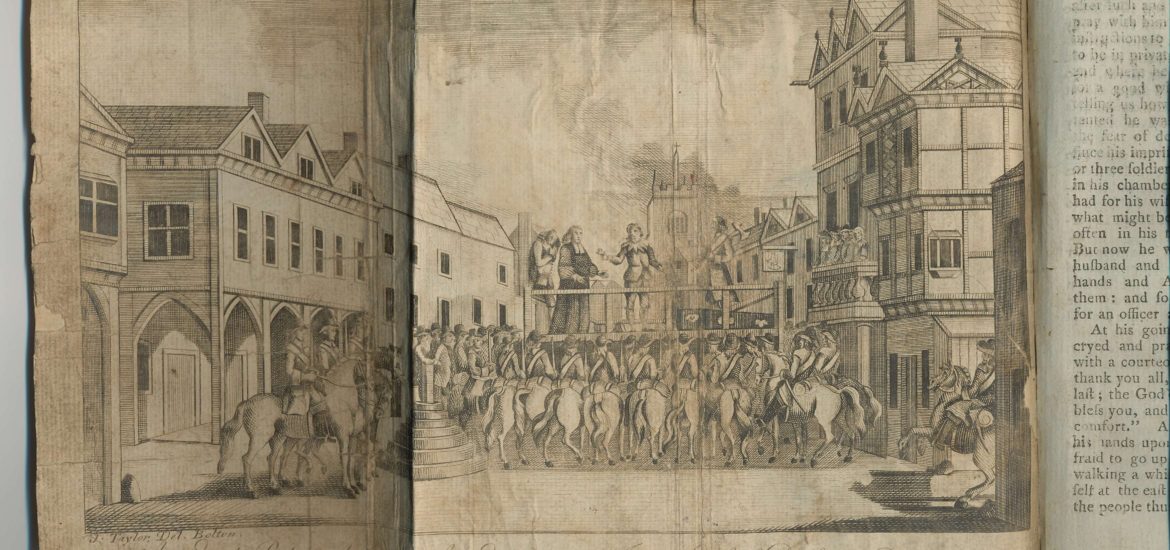

One of the first books to be published in Bolton was ‘A Description of Sieges and Battles of the Civil War’. Printed J Drake in 1785 it includes a picture of the execution of the earl of Derby in Churchgate, Bolton, in 1651.

This appears to be a line drawing showing the earl making his speech before his execution. On the right can be seen the Old Man and Scythe pub where he allegedly spent his final night. Next to that is the Swan where four people can be seen viewing the execution from a balcony. To the left is the old market cross with top; notice how the man is leaning on it. The only sign of movement is from a horse on its rear legs to the right of the picture at the entrance of Bradshawgate. Let’s look at another depiction of the moments before the earl’s execution.

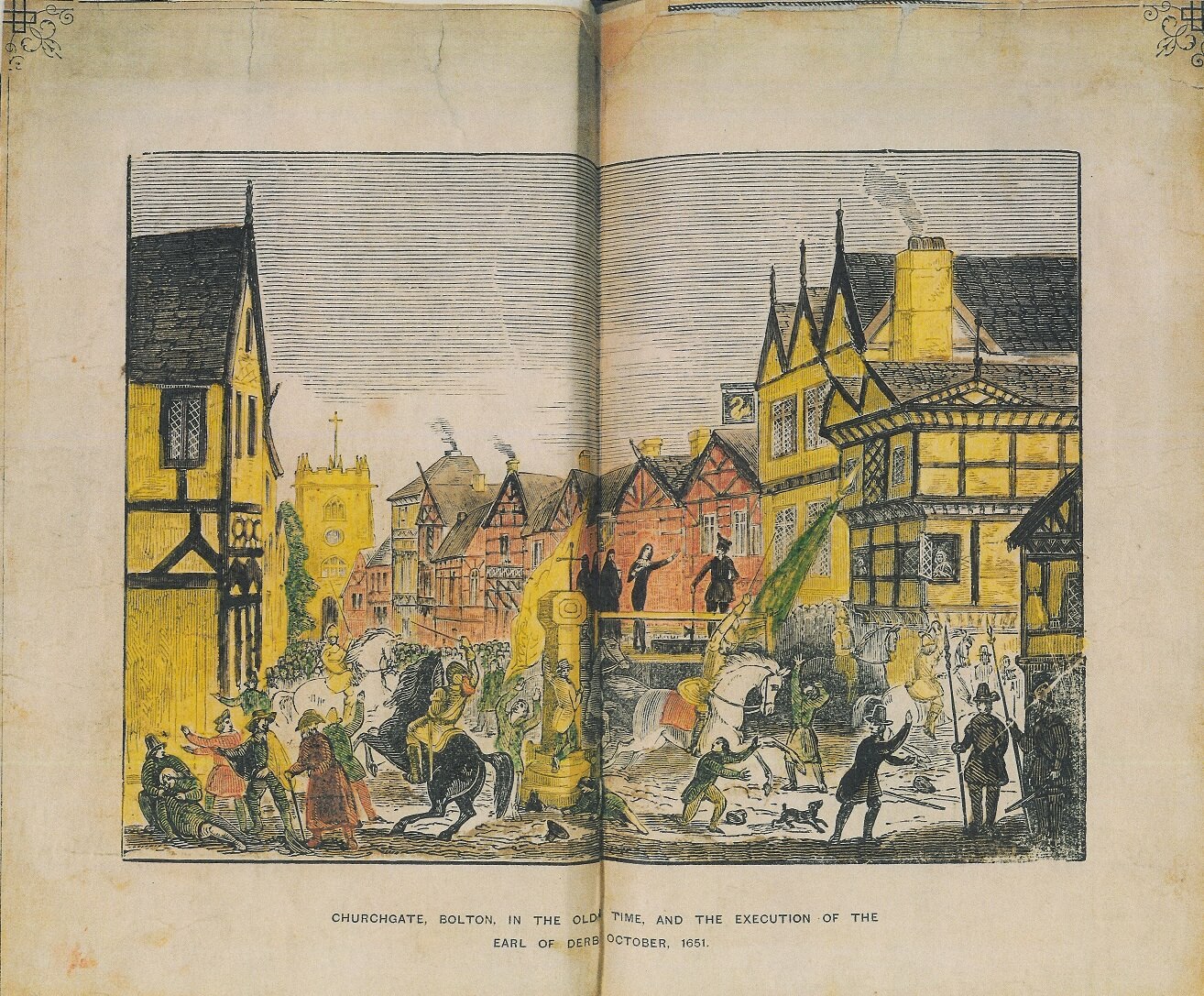

Notice how colourful this one is and how much more movement is in the picture. It’s drawn from a slightly different angle and in this image we get to see behind the scaffold where there is a large crowd, probably of the Bolton townsfolk. Notice how there is no balcony at the front of the Swan in this image though the buildings are similar. At the front it is chaos; people are running and a horse has unsaddled its rider. A soldier has his sword raised ready to strike people who seem to be protecting an injured person. Someone lays by the market cross as if they have been badly injured and hats are strewn all around with another soldier charging and about to strike a man. The market cross is different to the one depicted in the sepia picture. The sepia picture shows a covered walkway on the far left but none is shown in the colour picture. The only sign of grief in the sepia picture comes from the man on the left on the scaffold who appears to weeping into his hat. Yet in the colour picture those on the scaffold appear to be more controlled.

So, which one is the ‘true’ depiction of the execution? Well, both images are from the same book though different copies. As far as I am aware, the book had no colour images in it when it was first published which perhaps points to the colour one being a later addition.

The book describes the earl’s arrival for his execution:

Between twelve and one o’clock on Wednesday the 15th of Oct. 1851, the Earl of Derby came to Bolton with two troops of horse and one company of foot: the people every where praying and weeping as he went; even from the castle of Chester his prison, to his scaffold at Bolton, where his soul was freed from his body.

His lordship being to go to a house in Bolton, near the cross, and passing by it, said this must be my cross; then alighting and going into a chamber with some of his friends and servants, had, upon request, time allowed him until three o’clock that day, the scaffold being not quite ready, because the people of the town refused to strike a nail or to give any assistance to it; many of them saying, that since the war began they had suffered many and great losses, but never so great as this, it was the greatest that ever befell them; that the Earl of Derby their lord and patriot, should lose his life there, and in that barbarous manner…

At his going toward the scaffold, the people cryed and prayed on every side: His lordship with a courteous humility said. “Good people I thank you all, I beseech you pray for me to the last; the God of Heaven bless you, the Son of God bless you and God the Holy Ghost fill you with comfort.”

The earl then addressed the crowd in a lengthy speech which runs to about 5 1/2 pages in the book.

The copy of the 1786 edition held in Bolton Archives also includes an image of the execution of the Earl of Derby but this is strikingly different to the line drawing in sepia of the first edition. This is in full colour and shows a commotion at the front of the scaffold.

‘Then there arose a great tumult among the people; after which he said (looking all about him) I thought to have said more, but I have said; I cannot say much more to you of my good will to this Towne of Bolton, and I can say no more, but the Lord bless you, I forgive you all, and desire to be forgiven of you all, for I put my trust in Jesus Christ’.

What was the great tumult? Perhaps the community of Bolton was not united in its condemnation of the Earl of Derby despite his role in the Massacre of Bolton. This is further alluded to in an extract from a collection of gleanings in the local newspaper:

‘The most important dwelling 200 and more years ago was Kestor Fold, the residence of Dame Robinson, who prostrated herself at the foot of the scaffold on which James, the Seventh Earl of Derby was executed, Oct. 15th 1651, supplicating for the block on which the noble earl was executed. This block, tradition exerts, was buried within the grounds belonging to Kestor Fold in order, as Dame Robinson declared, the “malignants might never obtain a single chip” of it’.

One of the problems with written sources is that it is often from the opinion of the writer and the above extract is no different. Who was it who decided it was ‘the most important dwelling’? This was written during the Victorian era when the sympathies towards the Crown were perhaps more favourable than they had been at times during the seventeenth century. Even the book depicting the execution was written over 100 years after the event and there is no mention of a woman (or anyone) prostrating themselves at the block.

After the earl was executed his body was removed to the parish church with the intention of burying him in the parish church grounds. However, John Okey intervened to allow the earl to be interred in the family’s vault at Ormskirk Church and he also joined the ‘mournful procession a mile out of the town’. Unfortunately there is no further information on the ‘mournful procession’ nor how many followed the earl’s body. It is possible, that if a staunch puritan like Okey joined the procession that there were many others who also joined whether they were puritan or Royalist. It shows that there was some respect towards the earl but whether this was as a gesture of honour or some other reason, such as a disagreement over the execution, cannot be ascertained from such little information.

There is evidence of a form of retribution of the earl’s role in the Civil Wars. The block used for his execution was made from a tree on the earl’s Knowsley estate. This tree was where the earl supposedly sat watching as a captured Colonel Birch was dragged along by a haycart. Stanley’s executioner was George Whowell whose family had been killed in the ‘Massacre’. Family legend has it that he never spent the two gold coins given to him by the earl on the scaffold and the axe which was used in the execution was supposedly kept in the family until the 1800s.[1]

When the Restoration came, Whowell was killed when a group of royalist supporters cut off his head and stuck it on a pole, most likely in an act of retribution. There is a skull which is kept in the Affetside pub, the Pack Horse, which is supposedly George Whowell’s; one of the few reminders in the Bolton area of the ‘Massacre and execution’. Relics associated with the last hours of the earl were also kept. There was a chair in the Old Man and Scythe pub where the earl was said to have sat whilst waiting for the scaffold to be finished and a fish dish and a large Delft stone jug which the earl took a last small meal and a drink of water. There is a late sixteenth century chair which is still in the pub but the dish and jug have not been seen since the early eighteenth century.

[1] Massacre: The Storming of Bolton, David Casserly, p.173.